|

Art Lightstone Is it too Late to Stop Climate Change? In an article published in the New Yorker on September 8, 2019, Jonathan Franzen posed the question, "Why don't we stop pretending?" His subtitle added clarity to his hypothesis, suggesting that, "The climate apocalypse is coming. To prepare for it, we need to admit that we can’t prevent it." Given that title, one might assume that Franzen was saying it's time to give up on fighting climate change, and focus instead on preparing for it. However, that's not what Franzen ends up saying in the article at all. The article seems to explore the tension between two interrelated ideas: the notion that we are already beyond the point of no return and the notion that, even if we are beyond a tipping point, well.... we shouldn't give up fighting climate change. Based on the title, I do wonder if Franzen struggled with the overall message he wanted to convey to the public about climate change. In either case, his article raises an important question that is invariably on the minds of most people who are aware of and concerned about climate change. Namely: Are we too late? Is it time to give up on fighting climate change, and, instead, turn our attention to adapting to the challenges that will be presented by our new climate reality? Some say it is. Renowned naturalist and climate champion, David Attenborough, told the UN Security Council in February of 2021, "There is no going back - no matter what we do now, it's too late to avoid climate change... and the poorest, the most vulnerable, those with the least security, are now certain to suffer." Speaking of the various threats posed by climate change, Attenborough went on to say, "Some of these threats will assuredly become reality within a few short years." Attenborough is saying, in no uncertain terms, that certain dire impacts of climate change are now a certainty, However, that's not quite the same thing as saying that we've passed any particular tipping points. Tipping points, in the context of climate change, refer to a point where there is so much CO2, methane, and other greenhouse gases trapped in our atmosphere that climate change will keep progressing - at either a linear or an exponential rate - regardless of anything that human civilization could possibly do. There are now a number of climate scientists who question whether we may have already passed this climate tipping point. Dr. Timothy Lenton and Dr. Thomas Lovejoy are two such climate scientists. Dr. Thomas Lovejoy has studied the Amazon rainforest for more than five decades, and, based on his observations, he believes, "We are really right at that tipping point." A forest is classified as a "rainforest" if it generates something around 50% of its own rainfall. Such a phenomenon is made possible if the canopy of trees within a given forest exhale moisture upward through a process known as evapotranspiration, wherein moisture rising from the forest condenses in the cooler air above it, forming what is sometimes referred to as "rivers in the sky" that rain the precious moisture back down onto the forest. Sadly, this process is impeded as a forest becomes hotter, dries out, and no longer retains its moisture. Dr. Lovejoy points out that, "We see the signs in longer dry seasons, hotter dry seasons, tree species that prefer drier conditions gaining dominance over those that prefer wet conditions." Dr. Lovejoy is now of the belief that the Amazon rainforest, perhaps the most critical carbon sink for the planet's climate system, could transform from rainforest to savannah in a period of just ten to thirty years. If we lose the Amazon, then it's essentially game over for maintenance of the planet's current climate system, and, by association, for human civilization. The Tipping Point: Understanding the Difference between Climate Change and Runaway Climate Change I have often observed people conflating the notions of "climate change" with "runaway climate change," and this usually happens when folks are discussing the theoretical climate "tipping point." It's a simple-enough point to confuse. When people are discussing timelines regarding climate change, some people will have in mind a notion of avoiding climate change altogether, while others might have in mind a notion of avoiding the more serious issue of self-reinforcing, aka runaway, climate change... and people do not always take the time to clarify which notion they have in mind when they are discussing these ideas. So let's take a moment to really clarify the notion that we're exploring when we are discussing tipping points. As I mentioned above, the tipping point is a theoretical point in time, or, more to the point, a theoretical level of greenhouse gas concentration, or a theoretical level of warming, after which progressive climate change is essentially guaranteed - regardless of what human beings were to do after that point in time. In other words, it's a point wherein we would still see global warming progress, even if human civilization no longer produced a single gram of CO2, or any other greenhouse gas for that matter. In essence, it is in fact topping points that underpin the entire concern over climate change. This is because, if it were not for tipping points, then global average temperature would simply rise with increased greenhouse gases, but then diminish with decreased greenhouse gases. In other words, we could do wreck the climate today, but then fix the climate tomorrow by simply reducing global emissions of greenhouse gases. Sadly, this is not the case... and the reason is because of tipping points. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) first introduced the idea of tipping points a little more than two decades ago. "At that time, these ‘large-scale discontinuities’ in the climate system were considered likely only if global warming exceeded 5 °C above pre-industrial levels." (Lenton et. al, 2019). However, current IPCC reports now say that global tipping points could be reached at average global temperature increases as low as something in a range between 1 and 2 °C of warming (Lenton et. al, 2019). In their 2018 interim report on the state of the climate, The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), suggested that a global tipping point is fast approaching, and is likely to arrive around the year 2030 if we were to maintain a business-as-usual approach to carbon emissions. That report suggested that we would need to reduce global emissions of CO2 by 45% from 2010 levels by the year 2030 to avoid the worst impacts of climate change (p. 12). However, even this statement does not clarify whether 2030 merely represents a time frame to avoid severe climate change, or whether it represents a time frame to avoid runaway climate change. To make maters worse, even the ambitious targets outlined in the 2018 IPCC report are dependent on drawing down hundreds of gigatonnes of CO2 from the atmosphere every year. "All pathways that limit global warming to 1.5C with limited or no overshoot project the use of CDR on the order of 100-1,000GtCO2 [billion tonnes] over the 21st century" (SPECIAL REPORT: GLOBAL WARMING OF 1.5 ºC: Summary for Policymakers, 2018; C3). In that 2018 report, the notion of a tipping point was defined as, "A level of change in system properties beyond which a system reorganizes, often abruptly, and does not return to the initial state even if the drivers of the change are abated. For the climate system, it refers to a critical threshold when global or regional climate changes from one stable state to another stable state" (p. 559). A critical point to note is how the term "tipping point" is used throughout the 2018 IPCC report. In reading the report, one quickly observes that we rarely see the term "tipping point" used in its singular form. Rather, it is almost always used in its plural form - tipping points - thus conveying the notion that there are numerous theoretical tipping points at play within the climate system, as opposed to one omnipotent tipping point impacting the overall climate of the planet. What are Some Examples of Tipping Points? Examples of tipping points discussed in the 2018 IPCC report include mechanisms such as the albedo values of particular land masses, ice sheet melt, thawing of permafrost, as well as droughts and their associated forest dieback. Albedo Value Albedo value is a measure of a surface area's ability to reflect solar radiation. Albedo is essentially synonymous with reflectivity, so a high albedo value is associated with high reflectivity of solar radiation. Light colours, such as snow and ice, have higher albedo values and reflect more of the sun's energy than dark colours, such as forest and water. If you've ever walked from a white sidewalk onto a black asphalt driveway, then you know what I mean. We also experience this mechanism in action whenever we wear black T-shirts or white T-shirts on a sunny day. Sadly, if a regional albedo value falls below a certain point, that could permanently disrupt regional climate systems. Typically, but not always, heat leads to a loss of higher albedo surfaces and a gain of lower albedo values. The most critical example of this is melting glaciers and ice sheets. Snow and ice have the highest natural albedo values available, but they will reveal much lower albedo value surfaces, such as rock, earth, or water, when they melt. Ice Sheet Melt In a similar vein, polar ice sheet melt represents another tipping point. In this case, however, the melting of the ice itself actually begets further melting of ice. This is because ice sheets melt primarily from underneath, where an ice shelf floats on warmer water instead of resting on colder bedrock. The accelerating flow of ice melt and the ever-retreating grounding lines (where the ice sheet makes contact with land) together create a positive feedback loop. As an ice sheet melts, the ice shelf stretches out and become thin, which reduces its weight and allows the ice sheet to float further off its bedrock foundation. As the grounding line retreats and more of the glacier becomes waterborne, there is even less resistance underneath the ice shelf, and so the melting accelerates. As of 2014, studies by NASA and the University of California at Irvine suggested that the melting of the Antarctic was already past its tipping point. These studies suggest that the Antarctic will Thawing of Permafrost and Release of Methane The thawing of permafrost releases methane gas from what had been previously frozen ground. Sadly, methane is a powerful greenhouse gas. Thus, as more permafrost melts, it releases more methane, which warms the planet further, thereby melting more permafrost and releasing more methane. This may sound like no big deal, but it is. Studies estimate that the annual increase in atmospheric methane resulting from the melting of permafrost could be roughly equivalent to all the methane released into the atmosphere by the United States of America on an annual basis. The Water Cycle: Droughts, Forest Die Back, and Desertification Droughts, and the associated forest dieback, represents another theoretical tipping point. Droughts, sadly, lead to forest die-back, which leads to soil erosion and a reduced ability for land to support plant life or to retain moisture. As the world heats up, more land area converts from forest to savannah and then, eventually, to desert. As less moisture is retained in plant life and soil, the less land is able to hold onto rainfall when it occurs. Thus, rain simply runs off the land and back into rivers, lakes, and oceans. Worse still is the fact that a warmer atmosphere holds onto more moisture where it, as bad luck would have, acts as yet another greenhouse gas... and a powerful one at that. The 2018 IPCC Interim Report presents a table (Table 3.7 on page 264) which outlines a number of tipping points and what we might expect to see from these tipping points under three different global warming scenarios. Having said all that, the 2018 IPCC report also discusses a few "large-scale singular events" (p. 257) that have the ability to "result in or be associated with major shifts in the climate system." Four large-scales events identified in the 2018 IPCC report include:

Why we Should Keep Fighting While the data looks grim, I personally, whole-heartedly support the position that we are far from any point where we should even consider giving up on actively fighting climate change. In fact, I tend to take a rather simple approach to the notion that we might already be past any particular large-scale tipping point. Simply put, I downplay it. That's right... I downplay the notion that we might already be beyond a climate tipping point. I have decided to do this for three reasons:

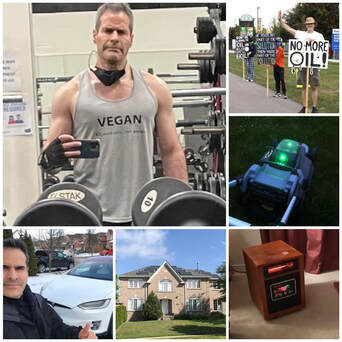

I suspect that people's attitudes regarding emissions are possibly not unlike popular attitudes regarding personal debt. Think of the number of people you know who respond to their anxiety about their mounting personal debt by simply taking on more debt. They do this because they really don't believe that they can ever be debt free... so they end up giving up, taking on more debt, and settling for a life of momentary pleasures and brief distractions from their debt worries. In my opinion, the way to avoid this self-reinforcing cycle is to never accept the notion that you are helpless... to never accept the idea that you can, if you choose to, climb your way out of debt. Interestingly enough, the concept of debt is often used to discuss climate change. Scientists, researchers, and modellers regularly use terms such as carbon budgets, investments, and withdrawals when discussing our climate predicament, and for good reason: the two ideas are indeed similar on many levels. Having said all that, I know that there are number of climate scientists, such as Kaz Higuchi, who advocate for the need to prepare for our new climate reality... and he's right, of course. Nobody can argue with that position. Climate change is already here, it's going to get worse, and the probability of significant climate change in our future - even runaway climate change - is probably in the majority. However, at this critical juncture, we still have so much opportunity to have a far greater impact on climate change through emission reductions than we will possibly be able to have in the future, and so I believe we must seize this opportunity.  Why wouldn't we do everything we can in the here and now to reduce our carbon emissions? Why wouldn't we do everything we can in the here and now to reduce our carbon emissions? That's why I'm pulling out all the stops in terms of emissions reductions. Whether it comes to lobbying the government to take climate action, directing my funds towards renewable energy and sustainable transportation, living a vegan lifestyle, or using electricity in the place of fossil fuels, I don't see myself as just one person who merely does or doesn't consume fossil fuels. Rather, I see myself as one experimenter... and one example. I've decided that, when it comes to climate change, if we have to go down, then I'd rather go down fighting. With that logic in mind, my family and I agreed long ago that we would be willing to take risks, experiment, try new approaches... all in an effort to see if it's possible to live a markedly carbon-reduced lifestyle. In most - but not all - cases, a number of these decisions wouldn't make economic sense if we were to perform a cost analysis based solely on our own economic outcomes. However, if we view climate change as a larger socio-economic issue that not only must be addressed for human civilization is to endure, but also implicates a number of hidden financial costs for all of us (such as increased costs for food, clothing, medical care, and even insurance premiums) then it starts to make a lot of sense. Beyond that, I also consider the impact that my example, as well as my insights, might have on others. Just like every individual on this planet, I can choose to be a person who will either have a positive or a negative influence on the dozens, or even hundreds, of people who know me. In turn, all of those people have the same choice to make, and, hopefully, they will amplify more of the positive examples they see for the dozens, even hundreds, of people who know them.

Each and every one of our actions do count. But, beyond that, each and every one of our actions can, and invariably will, set an example for others to follow... and that's where the real power of personal climate action lies.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Green NeighbourWhen it comes to the environment, we are all neighbours. Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed